Shared Decision Making

"For me realistic medicine is grounded in a conversation with a patient and family. The conversation needs time and working in the GP out of hours service is good for this as the consultation time is not limited by appointment slots. Sometimes it feels that this is the most important thing we do"Dr Jamie Hogg, Hospital Clinical Director Dr Gray's Hospital Elgin, Clinical Director Gmed GP Out of Hours Service, Grampian |

Shared Decision Making – Yes, I think I do that … but could you explain a bit about it?

What exactly is shared decision making?

Here is the 2021 NICE guideline definition2.

"Shared decision making is a collaborative process that involves a person and their healthcare professional working together to reach a joint decision about care. It could be care the person needs straightaway or care in the future, for example, through advance care planning. It involves choosing tests and treatments based both on evidence and on the person's individual preferences, beliefs and values. It means making sure the person understands the risks, benefits and possible consequences of different options through discussion and information sharing. This joint process empowers people to make decisions about the care that is right for them at that time (with the options of choosing to have no treatment or not changing what they are currently doing always included)."

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng197/chapter/recommendations#shared-decision-making

So, in other words … Shared Decision Making is a process which simultaneously combines the expert medical knowledge of the clinician with the expertise of the patient, who understands better than anyone else what matters to them and the relevance of their own values and priorities.

It involves sharing of evidence-based information about the options, benefits and risks and working together to agree on the most appropriate tests, treatments, management, or support packages. It’s relevant in any healthcare situation in which there may be different choices, including choosing to do nothing.

And most clinicians and most patients agree that providing more information, along with a move away from a ‘doctor knows best’ culture does help people reach more informed decisions.

I do it already, so why should I read this?

It’s true – most of us practice in this way already. But when patients are asked for their views, we might not be doing as well as we think we are!

It may be helpful to know more about how best to structure the conversation, how to explain risk and which phrases may lead to misunderstanding. And crucially, ways to ensure consultations do not become prolonged as a result.

Although we try to involve people as much as possible in their decisions and explain as much as we can, it’s well documented that clinicians can interrupt patients within 15-20 seconds of hearing their story3. and analysis of consultations shows that only 5% of the time is spent by the clinician answering questions4. Often not enough time is taken listening to and allowing the patient to talk about their ideas, concerns and expectations.

And one size does not fit all. Our recommendation might be the right thing in one sense but completely impractical or unwanted from the patient’s perspective. Usually our treatment should prolong life, decrease pain and improve quality of life. For some patients though, it may do the opposite. It’s a strange fact that doctors often choose less treatment or intervention for themselves than they would suggest for their patients5. Just because we can do something does not mean that we should, or that it is what the patient really wants.

OK, in a nutshell, how do I go about it?

First, this works much better when people are prepared. If there’s any information that can be shared ahead of the conversation, this gives the person time to think and means they aren't trying to take in new information and make decisions at the same time.

Inviting someone to accompany the person can also be helpful.

Sometimes it may be appropriate to send test results in advance and it’s also useful to encourage people to think about questions ahead of their appointment, e.g. It's OK to Ask or BRAN mnemonic:

- What are the Benefits of this test or procedure

- Are there any Risks or side-effects

- Are there any Alternatives

- What would happen if I did Nothing?

There are two useful (and similar) models for structuring a shared decision-making conversation.

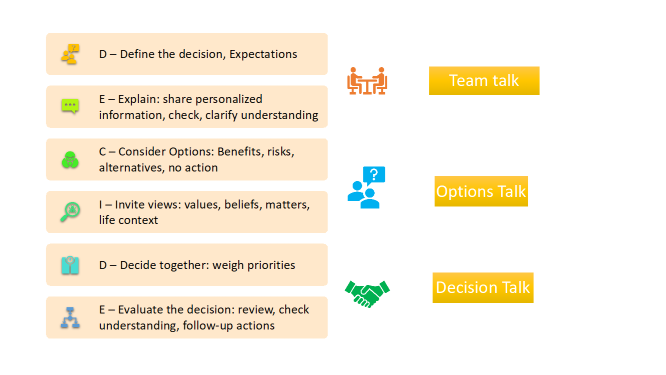

Below are two approaches to shared decision making. One is the DECIDE approach and the other commonly used approach the ‘3 talk model: Team Talk, Option talk, Decision talk’. They are closely linked.

The RED-MAP model is another approach that supports a shared decision making discussion and is often used when developing Anticipatory Care Plans with patients but can also be useful in other settings.

What’s the best way to present information?

Firstly, we need to consider how information is ‘framed’. ‘Gain framing’ is where the focus is on the advantages of intervention e.g. 95 out of 100 people having this procedure will have a good outcome. ‘Loss framing’ focuses on the disadvantages e.g. 5 in every 100 will have a complication.

It’s also easier to be consistent and stick with one ‘denominator’ – ideally 100 – and to say e.g. 5 in every 100 rather than 1 in 20; and rather than 1 in 4, say 25 in every 100.

Another way to express information in a helpful way is to talk about the ‘number needed to treat’. That is the number of people who need to have the intervention in order to have one positive outcome. In other words, if the number needed to treat is 23, this means that 23 people will need to have the treatment in order to have one good outcome. Conversely, the ‘number needed to harm’ is the number of people undergoing the treatment before a single harm occurs. If the number needed to harm is 200, this means that 200 people will have the intervention before one negative outcome (harm) occurs.

Another very useful decision aid is to have the information available as a ‘pictogram’ such as this one from NICE guidelines showing the effect of stopping smoking on preventing a cardiovascular event.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guideline development Group. Improving the experience of care for people using NHS services: summary of NICE guidance March 2012, BMJ (online) 344(mar16 1):d6422

Common pitfalls? Language to avoid?

Sometimes what we say can be misinterpreted, so here are some phrases to avoid and alternative suggestions.

|

Phrases to avoid |

May be interpreted as |

A better form of words |

|

What are your preferences? |

Perhaps I can ask for anything |

We need to think about your priorities (what matters to you) and then what we can do to fit with that

|

|

What are your goals? |

Are there targets I’m supposed to meet? |

What things are important for you to be able to do?

|

|

The test results are negative |

Oh dear, the results are not good |

There are no signs of any tumour in the tests we carried out

|

|

The ceiling of treatment is .. |

There’s a point at which I may not be entitled to treatment that might help |

There are things we can do but some treatments don’t work or help when someone has these health problems

|

|

We are going to withdraw treatment |

I am (or my relative is) being abandoned by the clinical team |

We are continuing care that may help but stopping treatments that are not helping and may cause distress or discomfort

|

It’s all very well in theory, but in reality, there isn’t enough time

One of the main concerns of clinicians is the potential for consultations to become longer, meaning that less people can be seen. And it’s true, consultations might take longer. But not much and not always. And there are ways to deal with this.

A Cochrane review6 looked across the medical scientific literature at effect of the use of decision aids on consultation length. They found 10 out of 105 studies on the subject, which looked at consultation length. Eight of the studies showed no effect on length of consultation and two studies showed an increase. Combining the data, the difference in consultation length overall was 2.6 minutes longer in the decision aid consultations.

Giving people information in advance of the clinic could also help. And potentially allows more time for considering the issues and asking the right questions.

But maybe we need to make more time. A more considered consultation may result in more people opting for a more conservative approach with less requiring subsequent investigation or procedures.

But do patients actually want to share decisions?

Fair point. Some people are wary of this, as they are used to the normal style where their clinician makes a recommendation and advice is generally followed. There is evidence to suggest that this view is more common among older patients, but there is an increasing trend for younger people (with ready access to multiple sources of information) to prefer the more informed approach of Shared Decision Making7 8. Remember also that there can be a significant ‘power imbalance’ in these conversations and some people find it difficult to speak up even when they want to be more involved in decision making.

Health literacy, the ability of people to access, understand, weigh up and use health information, is important The Health Literacy Place – Helping people in understanding modern healthcare. Many vulnerable people have lower levels of health literacy, but actually stand to gain the most from the greater opportunity to consider more information about proposed treatment6.

What about emergencies and people who lack capacity?

Shared Decision Making is usually not possible in true emergency situations when a person is seriously ill or injured and requires immediate intervention to preserve life.

Where a person temporarily or permanently lacks capacity, they should be supported to be involved in decision making. This may not be possible with the person themself but we should make every effort to find out a person’s likely wishes from people close to them or their Health and Welfare Power of Attorney.

Won’t people ask for treatment we can’t provide or wouldn’t recommend?

Health professionals are not required to provide care that is not indicated or appropriate or is not of overall benefit to the person. If someone is asking for an intervention that is not appropriate, try to explore their reasons in order to try to reach an agreement. We may sometimes need to ask for further advice or a second opinion.

Where can I learn more … and where’s the evidence for all this?

The national Realistic Medicine Website can be found at Realistic Medicine – Shared decision making, reducing harm, waste and tackling unwarranted variation

Public resources and information regarding shared decision making can be found at It's OK to Ask | NHS inform

There is a very good on-line module available for staff on the TURAS learning site.

- Decision making and Consent: guidance on professional standards and ethics for doctors. The General Medical Council. November 2020.https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/updated-decision-making-and-consent-guidance_pdf-84160128.pdf

- Shared Decision Making. NICE guideline (NG197) June 2021 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng197/chapter/recommendations#shared-decision-making

- The effect of physicianbehaviouron the collection of data. H B Beckman, R M Frankel. Ann Intern Med.1984 Nov;101(5):692-6.

- Patient participation in the cancer consultation: Evaluation of a question prompt sheet. P. N. Butow, S. M. Dunn, M. H. N. Tattersall & Q. J. Jones. Annals of Oncology 5: 199-204, 1994.

- Physicians Recommend Different Treatments for Patients Than They Would Choose for Themselves. P A Ubel, A M Angott, B J Zikmund-Fischer. Arch Intern Med. 2011: 171(7): Arch Intern Med. 2011 Apr 11; 171(7): 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.91.

- Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Dawn Stacey et al.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr; 2017(4): CD001431.Published online 2017 Apr 12.doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5

- Removable retention: enhancing adherence and the remit of shared decision-making. Al-Moghrabi, D., Barber, S. & Fleming, P. Br Dent J 230, 765–769 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-021-2951-x

- A Mobile Phone App to Support Young People in Making Shared Decisions in Therapy (Power Up): Study Protocol. Chapman L, Edbrooke-Childs J, Martin K, Webber H, Craven MP, Hollis C, Deighton J, Law R, Fonagy P, Wolpert M

JMIR Res Protoc 2017;6(10):e206

doi: 10.2196/resprot.7694PMID: 29084708PMCID: 5684513

Adapted with kind permission from Alastair Ireland, Realistic Medicine Lead, NHSGGC and Claire Macaulay, Realistic Medicine Lead, NES

Published: 10/11/2021 16:25